Cognitive Benefits of Playing Video Games

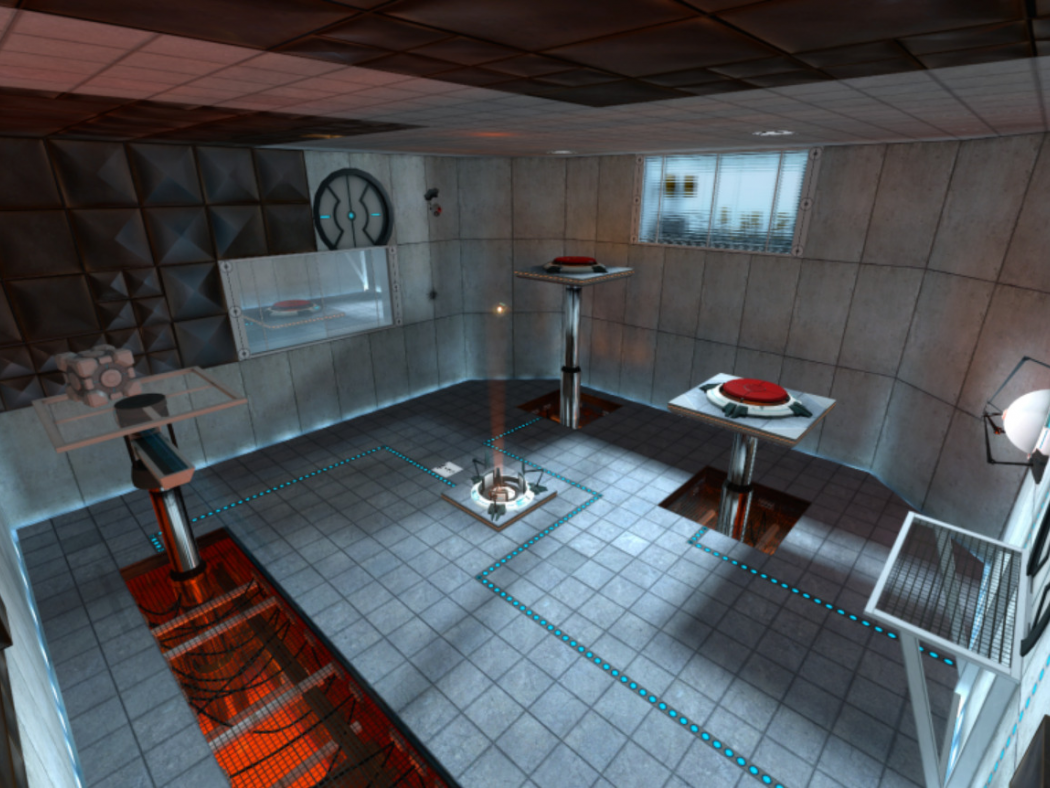

Take a moment to examine the following scenario: you’ve entered a square room with two raised platforms on your left, some scaffolding on your right, and a door directly across from you, all of which can’t be reached from the ground. The platforms each have a switch on them that must both be held down to activate the door, and there’s a weighted cube on the scaffolding needed to hold one of them down. In the center of the room is an energy receptacle that will cause the scaffolding to move back and forth, but the power source is a linear ball of energy traveling perpendicular to the receptacle’s opening. The only tool at your disposal is a device that creates a wormhole between two specified points in the room, but the layout of the room affects which points you can use. How do you proceed past the door?

This is one of the puzzles presented to you in Portal, a physics-based video game that tasks you with trying to escape from a rogue Artificial Intelligence by progressing through a series of rooms designed to be impassible without the handheld portal device in your possession. The game encourages you to “think with portals” in order to solve each room and progress through the game, making use of (and bending the rules of) physics, math, logic, spatial reasoning, probability, and problem-solving to do so. It was designed as entertainment, a fun way to unwind after a long day of work or study, so it might not seem like the sort of medium that would train your cognitive skills. However, that is exactly what the game’s sequel was found to do when a study at Florida State University compared it to Lumosity, a game designed specifically for brain-training. In a surprising turn of events, people who played Portal 2 actually showed greater improvement on cognitive skill tests after playing it than people who played Lumosity.

Why would a game meant to be played in one’s spare time offer greater cognitive improvement over a game specifically designed to improve brain function? The answer lies in neuroplasticity, which is the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections over the lifespan. When areas of the brain are engaged through gameplay, a process called “axonal sprouting” occurs, causing the axons in the brain to create new neural pathways to accomplish a needed function. While Lumosity’s mini-games are designed to train individual cognitive functions, Portal 2’s gameplay engages multiple cognitive processes at once. The result is that Portal 2’s gameplay, which utilizes more brain processes in order to accomplish tasks in game, creates neural pathways that enable more complex tasks to be accomplished.

Portal 2 is not an isolated case either. According to the American Psychological Association (APA), gameplay has an effect on cognitive function by strengthening a player’s spatial navigation, reasoning, memory, and perception. In a paper published in their journal American Psychologist, researchers found that players of first- and third-person shooter games developed an improved ability to think about objects in three dimensions, a useful trait for students engaged in STEM-related fields. Children who played strategic role-playing games were found to have improved problem-solving skills, and benefited from increased creativity regardless of the type of game they played. Another set of studies found that gamers who played action games between 5 to 15 hours each week were more able to pick out details in cluttered environments, and on average were better at keeping track of multiple objects (six, versus the average of three) and multitasking with increased speed while maintaining accuracy.

The benefits go beyond honing cognitive functions: video games have been shown to be an effective treatment for several cognitive disorders as well. According to a Psychology Today article, non-gamers with the condition amblyopia, which causes one eye to become essentially non-functional, who played video games using only the affected eye showed improvement to the degree that the eye recovered to normal or near-normal functioning. Action games were found to reduce impulsiveness, based on a test of the ability to refrain from responding to non-target stimuli. In elderly subjects, video game play was associated with a reduction in mental decline that is associated with aging, as well developing better self-concepts. Gaming has also been found to combat dyslexia in some cases: one study found that as few as 12 hours of game play improved scores of reading and phonology tests with children, with improvement equaling or exceeding that achieved by training programs designed to treat the condition.

So should you start playing video games to gain these cognitive benefits? The simple answer is: if you want to. While video games are readily accessible to most people with a computer or smartphone, not everyone wants to play them, and there are many other methods to gain the benefits associated with game play. As new gaming technologies emerge, such as virtual and augmented reality systems, new research on how they affect our mental functioning will need to be conducted to determine if the currently associated benefits, other benefits, or even detriments arise in their usage. Regardless of whether you decide to play or not, what’s important is that you enjoy the method you use to train your brain.